|

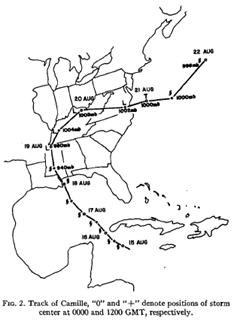

The mountains in the East can play a significant role in focusing lifting along the windward slopes of the rising terrain.† Storms crossing the mountains or interacting with them that come from west or east of the mountains can produce heavy rainfall along the east slopes of the mountains. Camille is the poster child of storms that produce catastrophic rainfall when they interact with the Appalachians.† More than 150 people died as a result of flash flooding and mud slides caused by the heavy rainfall associated with Camille making it the worst natural disaster in the history of Virginia (Schwartz 1970).† Over 27 inches of rainfall was reported during Camille and much of it fell in a 6 hour period. Remnants of Camille definitely helped focus rainfall but terrain was not the only factor that led to the heavy rainfall. |

|

Hurricanes and the Appalachians |

|

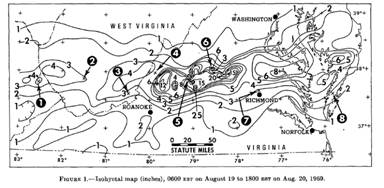

The maximum in rainfall occurred north of the track of the surface low in a region where low level southeasterly, and then easterly, flow was intercepted by the mountains.† However, when you compare the orientation of the mountains to the orientation of the axis of heavy rainfall, there was a difference.† Other focusing mechanisms must have been present to account for the differences in the orientation. One of the difficulties predicting rainfall near the mountains in the Mid Atlantic Region and northeast is that there also is often a front, jet streak or upper level trough that will also be contributing to the lifting and ultimate rainfall pattern.† |

|

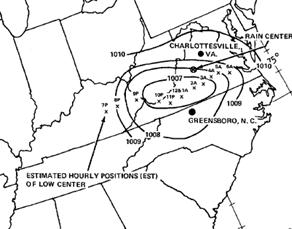

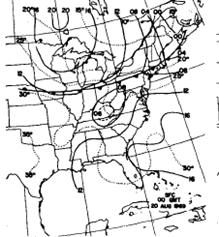

Mean Sea Level pressure chart for the period 2200 to 0300 EST on August 19-20, 1969.† The dots are hourly positions of the low starting at 7PM EST. |

|

A closer look at Camille helps explain why the precipitation axis was oriented east-west while the terrain had a more southwest to northeast orientation.† At 7:00 PM EST the remnant circulation was located over eastern Kentucky with the low being well defined on the satellite imagery (not shown). The remnant low tracked almost due east across Virginia with the bulk of its precipitation falling north of the low.† The low was forced eastward under the trough that was dominating the Northeast and was forced eastward along the right entrance region of an upper level jet streak (see below) |

|

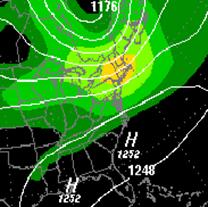

200 hPa analysis valid at 00 UTC 20 August 1969.† |

|

200 hPa analysis valid at 12 UTC 20 August 1969 |

|

From Schwartz 1970 |

|

From Schwartz 1970 |

|

From Chien and Smith 1977 |

|

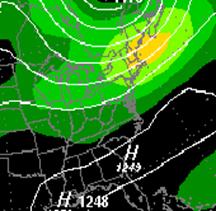

Sea level pressure (contour interval=4 mb) and surface temperature (contour interval=5oC) valid 00 UTC 20 Aug 1969 |

|

Sea level pressure (contour interval=4 mb) and surface temperature (contour interval=5oC) valid 12 UTC 20 Aug 1969 |

|

As the low shifted eastward, there was a significant tightening of the surface temperature gradient across PA to the east of the surface low.† In all likelihood,† the jet streak and the remnant low were acting synergistically to produce frontogenesis.† Chen and DellíOsso (1987) have noted that diabatic heating associated with heavy rainfall has an impact on strength of the upper level jet and its associated transverse circulations (see below).† In their study,† diabatic heating increased the strength of the ageostrophic circulation associated with the upper branch of the jet even as the latent heating increased the strength of the winds within the jet streak itself.† Latent heat also increases the low level convergence and frontogenetical forcing along any thermal boundary.† The tightening of the low level thermal gradient across Virginia suggests this synergistic interaction took place which probably contributed to re-energizing the storm.†† The jet streak and terrain both probably enhanced the lifting.† Atallah and Bosart (2003) have noted that the effects of latent heat on the upper level structure in the vicinity of a tropical system may at times have significant errors.† |

|

The jet streak and terrain may explain a large portion of why rainfall amounts were much heavier east of the mountains than west of them.† However,† the differences in precipitation may have also resulted from the typically nocturnal fluctuation that often occurs with the remains of old storms.† Convection associated with tropical systems typically flares up during the night.† The important thing to remember is not to give up on a stormís potential when it still has a well defined circulation,† as it crosses the mountains,† precipitation may enhance significantly.†† |

|

From Chien and Smith 1977

|

|

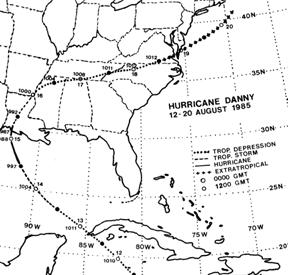

Hurricane Danny is an interesting storm to contrast with Camille.† It too came ashore in the central Gulf of Mexico and then tracked around the periphery of the subtropical ridge and produced heavy rainfall on the east sides of the Appalachians.† |

![[.png Graphic]

Wind Barbs, Wind Speed (shaded) [Knots]\ Geopotential Height Contours [gpm]\1000 mb - 12Z Sat 17-Aug 1985 and TMPprs

Size: 51 Kb](image20571.jpg)

|

850 hPa and 1000-hPa temperatures v.t. 12 UTC 17 Aug 1985

|

![[.png Graphic]

Wind Barbs, Wind Speed (shaded) [Knots]\ Geopotential Height Contours [gpm]\1000 mb - 00Z Sun 18-Aug 1985 and TMPprs

Size: 47 Kb](image20641.jpg)

|

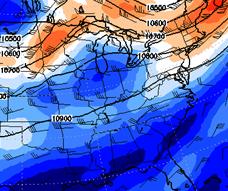

250-hPa heights and winds v.t. 12 UTC Aug 1985 |

|

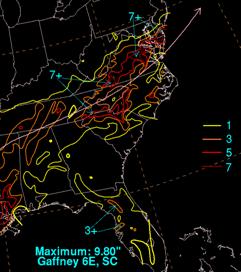

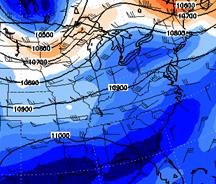

Like Camille,† Danny produced heavier rainfall east of the mountains than west.† Where Danny differed was in the strength of the upper level jet across the Mid Atlantic region.† This jet streak actually weakened as Danny approached (see below).† Danny also had a secondary precipitation maximum along the east slopes of the Appalachians south of the track of the storm where there was strong speed convergence present at 850-hPa (see figure below).† |

![[.png Graphic]

Wind Barbs, Wind Speed (shaded) [Knots]\ Geopotential Height Contours [gpm]\1000 mb - 12Z Sun 18-Aug 1985 and TMPprs

Size: 49 Kb](image20681.jpg)

|

850 hPa and 1000-hPa temperatures v.t. 00 UTC 18 Aug 1985

|

|

250-hPa heights and winds v.t. 00 UTC 18 Aug 1985 |

|

850 hPa and 1000-hPa temperatures v.t. 12 UTC 18 Aug 1985

|

|

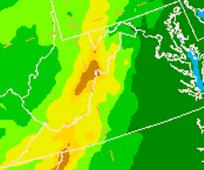

Danny produced a rainfall maximum along the east slopes of the mountains just north of the stormís track.† It also produced a stripe of heavy rainfall with another maximum near Richmond in an area where the gradient in the isotherms increased.†† Even without a strong jet streak,† if a storm holds together and has a decent 850-hPa circulation while crossing the mountains,† it still may produce heavy rainfall.† |

|

From Chen and DellíOsso, 1987 |